This blog post was written by Michael Gismondi, a current graduate student at Saint Vincent College enrolled in my course, Reading, Writing, and Differentiation in the Content Area. Read more about Michael at the end of the blog.

As teachers, we often tend to look at vocab from a boring and bland “square” perspective. Students take vocab from a book, copy down the definitions, and then move on to the next one until their homework is done. This is the tried and true vocab method that has stood the test of time. The “square” method. Straightforward with no unexplained twists and turns. And why would we change it if it works right? Well, it doesn’t.

Time and time again, studies have shown the importance of how students learn vocabulary. More recent studies have looked at the different tactics employed by teachers, and how these different strategies affect student performance. These studies have shown that the modality in which you learn the vocabulary contributes significantly to performance on standardized tests (Zhang & Xiaofei 2015). In short, understanding the vocab words and their meaning leads to understanding the content and other uses of those words outside of it, and the method in which you practice and memorize the vocab matters. We all know that having a comprehensive vocabulary leads to student success later in life. However, students are coming to class with less and less vocab these days than ever before. The tried and true method of copy and paste doesn’t work, and it never really did. We aren’t teaching them the vocab, we are teaching them how to rewrite words in a textbook for a grade. And be honest and ask yourself, did you really enjoy or learn much from writing vocab back when we were in school? Absolutely not! So why are we making students still do it today?

As teachers, we need to reinvent how we do vocab in our classrooms to give students a word bank for life, one that goes further than the definitions in textbooks. We need to think outside of that “square” box, and look to something fresh and new to ensure our students are leaving our classrooms with a vocabulary that far exceeds what they came to us with. However, getting students to go outside of their comfort zone isn’t always easy, and it often requires us to go outside of our comfort zones as well. A concept that terrifies even the most experienced teachers. So, to make this easier on all of us, let’s get rid of the boring “square” and look at something new yet familiar. How about a triangle?

Vocab Triangles are a strategy that teaches students the definition of words by using them in a sentence that helps them draw connections to other words. It helps students not only memorize but also apply vocabulary words in a meaningful way that establishes personal connections through the sentences and stories that they tell. Now you may be thinking, “How

can you do all of that with a triangle?” It’s actually really simple, and it’s really fun to see what kinds of stories your student can create when given three words and their imagination.

How Do Vocab Triangles Work?

Preparation

Step one is to pick out the vocabulary your students need to know from your lesson. This could be as simple as the vocabulary words at the beginning of a section or chapter. But I challenge you to go further than that. Think of complex words that students may or may not know that they are going to encounter in the text. Think of what those words mean in relation to your content, and how familiar your students may be with them outside of your content area. Find words that expand your students’ vocabulary beyond those highlighted words we hated in our textbooks growing up.

Next, think about your classroom setup and your students’ needs. You could have them do this activity working independently, with a partner, or in a group. So, pick as many words as you need according to your class size and student needs. Feel free to double up on words for different groups. Just try to make every sheet as unique as possible without the same three words being on two different sheets. You could even give students the blank template and write the words on the board for them to choose. Just try to ensure all words are chosen so all words can be covered.

Changing the shape of vocab

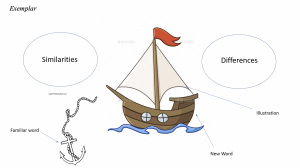

Give them an example on the board using your own triangle and words. Draw the triangle and put one word in each of the three corners. Take one word connected to another by one side of the triangle and make a sentence out of the two words.

Have the students make the other two connections as a class. Finally have the students use the sentences you made together to tell a quick 1-2 sentence story that uses all three words.

Let them make their own connections

Give students short definitions of the words. They don’t have to be the exact dictionary definitions, just enough that they know the meaning and can draw connections.

Give the students or groups their triangle to work on. Give them some time, about 10 minutes, to work out their definitions and connections. Have them form the final sentence on their own before bringing everyone back as a group.

Share their stories

Have students or groups share what they wrote with the class. This can help students make further connections to words as well as give you opportunities to clear up misconceptions in the class. Be sure to expand upon definitions where needed to ensure full understanding.

What comes next?

The next step is modifying it to cater more towards your classroom or content area. For example, in my content area of history, you could modify this by extending it beyond vocab. First have students make sentences and a story using the provided vocabulary words. Then go over those connections with the students before teaching a lesson that incorporates the vocab. Once the lesson is finished, have students revisit their old sentences, reflect on them, and write new ones that connect those words within the content you just taught. This will help reinforce the vocab definitions, connect them to the content, and ensure all misconceptions from the earlier activity, if any, were cleared up. If the sentences are short enough, you could even have students make a mnemonic device to help them remember the sentences when trying to memorize or recall the definitions of the words.

Although vocab triangles are primarily for vocab, they also have applications far beyond simple application of key words. Another thing you could do is have students connect main ideas of a text, themes in a story, or big ideas within a unit using the triangle format. Simply choose three themes and see how your students make connections between them. This could be a great way to review old information or prepare students for an upcoming exam.

The vocab triangle could also be used as a brainstorming activity or outline for an essay. Have students place their core arguments or body paragraph topics in the boxes and use the lines between them to draw connections between their ideas. This could help students explain their thinking, expand upon their ideas, and stay organized when writing an essay.

You could even use something called the Triangle Model. Instead of having students write sentences that connect to other words, break down the triangle into three tiers. Tier 1 would be the bottom of the triangle in which students write words and its definition. Tier 2 would be the middle of the triangle where students can write words that fall within a words word family. And tier 3 would be the top where students could draw a picture that describes the word. This method helps students associate the word with other words, and the picture they draw can help them recall the definition later on.

So please, for the sake of your current and future students, ditch the copy and paste homework and step outside of the “square” vocab box that so many teachers find themselves in.

References

Zhang, Xian, and Xiaofei, Lu. “The Relationship Between Vocabulary Learning Strategies and Breadth and Depth of Vocabulary Knowledge.” The Modern Language Journal, vol. 99, no. 4, 2015, pp. 740–753., http://www.jstor.org/stable/44135292. Accessed 30 Mar. 2021.

About the Author

Michael Gismondi is a Graduate Student enrolled at Saint Vincent College. He obtained his Bachelor’s in History with a minor in Medieval Studies from Saint Vincent, and he is continuing his education in pursuit of his Masters in Curriculum and Instruction as well as his secondary certification in social studies. His goal is to help emerging students study and understand history as it pertains to them and their lives, and help them understand how to apply social studies to the topics around them. He believes that by studying history, students can better explain the world around them through the lives and experiences of the people who came before.